BLOGG Contemplating a Digital Periegesis

by Anna Foka (Uppsala University), Elton Barker (The Open University), Kyriaki Konstantinidou (Umeå University) and Johan Åhlfeldt (University of Gothenburg)

The Periegesis Hellados of Pausanias of Magnesia – the Background

The Periegesis Hellados (Description of Greece) is the work of a certain Pausanias of Magnesia, a writer of the 2nd century CE. Unlike contemporary tourist guides or other late antique narratives of pilgrimage, Pausanias shows little interest in describing the natural environs or infrastructure (roads, bridges, etc.) through and over which he undertakes his journey. Instead, his ten-book-long narrative reveals a highly selective and idiosyncratic description of Greece based on its human footprint.

Pausanias famously begins his description with no introduction: we aren’t told who he is, what this text is, or why he’s writing it. About two thirds of the way through his first book, however, he mentions in passing what seems to be his working method. He has set out to record the man-made monuments in and human history of the landscape:

“Such in my opinion are the most famous legends (logoi) and sights (theorêmata) among the Athenians, and from the beginning my narrative has picked out of much material the things that deserve to be recorded.” (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.39.3).

Sights (theorêmata in Greek) is etymologically connected to theôria, a word deriving from the combination of thea (view) and hôran (to see). Theôria has this double sense of looking at something and holding it in one’s mind to look over, or the ability to behold a sight and contemplate its meaning simultaneously. Theôria is a core concept in Greek literature and culture. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle praises the theoretical life (theôretikos bios) on the basis that it entails a supreme virtue of mind.[1] He describes the contemplation of art, religious temples, or important sites, for example, as a pleasant, self-sufficient and leisurely activity that is distinctly human, which he regards it as higher than ethical or political activity.[2]

Theôria has been at the heart of ancient historiographical and geographical writing from its beginnings. From Herodotus’s winding path through different peoples and places to piece together their related histories (1.5) to the man in the Odyssey who “saw the cities of many men and knew their minds” (πολλῶν δʼ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, Homer, Odyssey 1.3), the connection between vision and understanding is a recurring theme. During the late antique period (c. 200 to 900 CE) and toward the early modern period, geographies of many different sorts appear in nearly every type of writing as well as in multiple languages (Greek, Latin, Syriac, Armenian, and others), facilitated by the cultural and ethnic diversity of the Roman Empire, as well as by its lines of communication. A common element in these texts pertaining to the “inhabited world” (oikoumenē) is the use of description to contemplate (theôrizein)—and to collect and organise—knowledge.[3] The Periegesis appears to encapsulate this aesthetic by virtue of representing a sense of movement through space (and time) that reproduces contemplation of the landscape and its stories, or in other words a “discontinuous and anachronical exploration of the Greek past and present through its monuments and remains".[4]

The word Periegesis derives from periēgeisthai, “to lead or show around”. This double sense of movement (through space) and description (of place) is to identify and reflect on not only how Pausanias describes and contemplates places and objects within them, but also the spatial organisation of his narrative theoria—how he relates places to each other and contemplates on their relation. While Pausanias represents a theoria of ‘Hellenism’ in the auspices of the Roman Empire, the books are especially informative in relation to space and cultural diversity. Pausanias, ‘inhabited an era when the notion of ethnic identity, particularly that of the Greeks, was in a state of ambiguity’,[5] as Greece was under Roman rule at the time. For our project (www.periegesis.org, funded for three years by the Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Foundation) we aim to digitally annotate the text in order to trace, map, analyse and visualise Pausanias’s spatial theoria: his (re)imagining of Greece.

The Digital Periegesis’s technical environment

Usability and reach are the determining factors behind our choice of how to produce a digital Periegesis, though other important factors like efficiency, sustainability, collaboration, and transparency have also played a role. Too often new initiatives in the so-called “digital humanities” devote time and resources to building self-standing, new applications. We have taken a contrary approach that puts the emphasis on the reuse and extension of data and tools that have already been produced and have a community around them. While this means working closely with other groups, we believe that the Digital Periegesis will greatly benefit from being located within a landscape of like-minded resources, as well as enabling us (and other collaborators) to concentrate on our aims in this project: to identify and explore the spatial form of, and the forms of space within, Pausanias’s narrative.

There are three key background elements to our digital exploration of Pausanias. First, we use the text of the Periegesis from the Perseus Classical Library (specifically from their newly launched Scaife viewer).[6] We use various forms of the text: its plaintext format for the English translation, and the TEI text for the Greek. While the translation of Pausanias can be considered rather outdated, both of these texts are openly licensed (in CC-BY) and free for reuse. The benefits of being able to take the text and (re)use it as the basis for digital analysis far outweighs other considerations (such as of accuracy of contemporary English idioms), particularly when we are focused on analysing specific features within it (the category of place and other spatial concepts).[7]

The second key element is the platform in and with which we explore the text itself, the open-source, Web-based platform Recogito (https://recogito.pelagios.org). Recogito enables the user to easily upload texts (as well as images and tables), which can then be annotated with additional information. In particular, Recogito has been designed with place as the primary entity for semantic annotation. Using a network of global authorities on place information (aka digital gazetteers), Recogito enables the user to not only identify a character string such as “A-t-h-e-n-s” as a place, but also then to align that reference to an appropriate gazetteer, so that a user, for example, can disambiguate between the “Athens” of Pausanias’s period and “Athens, Georgia”, the hometown of the band REM. As part of a growing community, Recogito currently has c. 3,000 regular users, who have produced c.1.90 million annotations. Having uploaded our different versions of Pausanias’s ten books to Recogito to work on directly, we are creating semantic annotations to do with place, which essentially treat the text itself as a database of information.[8]

Third, and following on from this, semantic annotation in Recogito conforms to a Linked Open Data model for connecting online resources. The two-step process of annotation noted above—where one asserts that a character string in the document represents a place entity and then aligns that reference to the global authority gazetteer on that place—enables the creation of a data format known as RDF, which is one of the outputs that Recogito produces. This means that by working on Pausanias in Recogito we will be able to connect our Digital Periegesis to other resources that hold information about the places referenced in the text. This will, in turn, enable the comparison of Pausanias’s deep description of various sites (the Athenian Agora, or Corinth, for example) to the archaeological data found there and the plans of them produced in modern research.

In addition, the possibilities of semantic annotation enabled by Recogito go far beyond the relatively simple identification and alignment of an individual place. As we explain below, it can also capture other spatial forms, beyond toponyms.

Creating an ontology/typology for semantic annotating the Digital Periegesis

Our aim is to identify and explore the spatial form of, and the forms of space within, Pausanias’s narrative. To describe and to contemplate a place, to theorize it, requires establishing a set of concepts and categories that can capture as much information as possible about those places in Pausanias’s writing, how they function within his narrative, and, in turn, how his narrative is constructed through spatial description. This means not only identifying a place as an entity, but also capturing other spatial forms (description of those places, locatives for placing the reader in the landscape, peoples representing places, objects in space, etc.), and the relationships between them (the connections between places, peoples, and objects in a semantic unit, such as a sentence), as well as other important narratological features (such as focalisation or changes in time period).

To develop a robust method for semantically annotating Pausanias, we have worked on two case studies which provide different perspectives on the process. One case study has focused on annotating a section of the text—the first 15 sections (paragraphs) of Book 2 on Corinth—to get a sense of the narrative construction of space and place. The other case study has focused on one particular place—Delos—and annotated all sections related to it, to get a feel for how a single place can be represented across the work as a whole. With a view to building a method that can help us annotate in a systematic and uniform manner, we have so far developed the following semantic annotation typology based on the entity and tagging feature in Recogito:

- Entities

Recogito provides three choices of entity: place, people, and event. Our primary concern is place: when we identify a place in the text, we mark it and align it to an appropriate gazetteer entry (if we can find one). However, it will also be important to identify people in the text, especially for their role in certain places (or even as proxies for place): for this we use the “people” entity (and both the “place” and “people” entity if considered to be representing a place).

- Tags

Recogito also provides a “free” tagging features, which enables users to provide more information about those entities and construct their own schema for labelling them. For instance, for places, we want to identify: Is the place human, physical, regional, or mythical; and what type of place is it? For example, a human place might be a settlement, temple, or assembly. For people, are they mythical or historical; divine or mortal; male or female; Greek or other? Or are they a proxy for a place?

- Relations

Fundamentally, we are interested in capturing the ways in which Pausanias constructs his description of Greece. There are various different kinds of spatial relationships that can be defined in the text, as Pausanias moves through both space and time. They are:

- Topographic: a place in space, as Pausanias moves through the landscape;

- Chronotopic: a place in time, as Pausanias moves through the history of a particular place/building/statue; or

- Analogic: places compared, as Pausanias relates one place to another in a different part of the world.

We use the “event” entity to highlight the sections of the text in which either of these three descriptive modes take place, and use the tagging feature to then specify the mode (topographic, chronotopic, or analogic). We can also use an additional relational tagging feature, which is part of the Recogito UI, to further define those relationships: e.g. are the topographic relations being described as synoptic (a bird’s eye view) or hodologic (movement through space)? A further tag can be used to define focalisation–whether the description is from the narrator’s viewpoint or the perspective of another.

Initial observations on the affordances and challenges of text mapping

The application of digital mapping does not remove the complexities associated with traditional cartography, and even introduces new challenges to the visualisation of spatial data and interpretations. While traditional print cartography can only visualize place as static geometries on a map, digital platforms provide a capacity for easily distributed updates, interoperability, and interactivity. By connecting references to an open source internet mapping subset of the ancient world, we were able not only to identify but also to instantly visualize locations mentioned in relation to other locations, people, or objects.

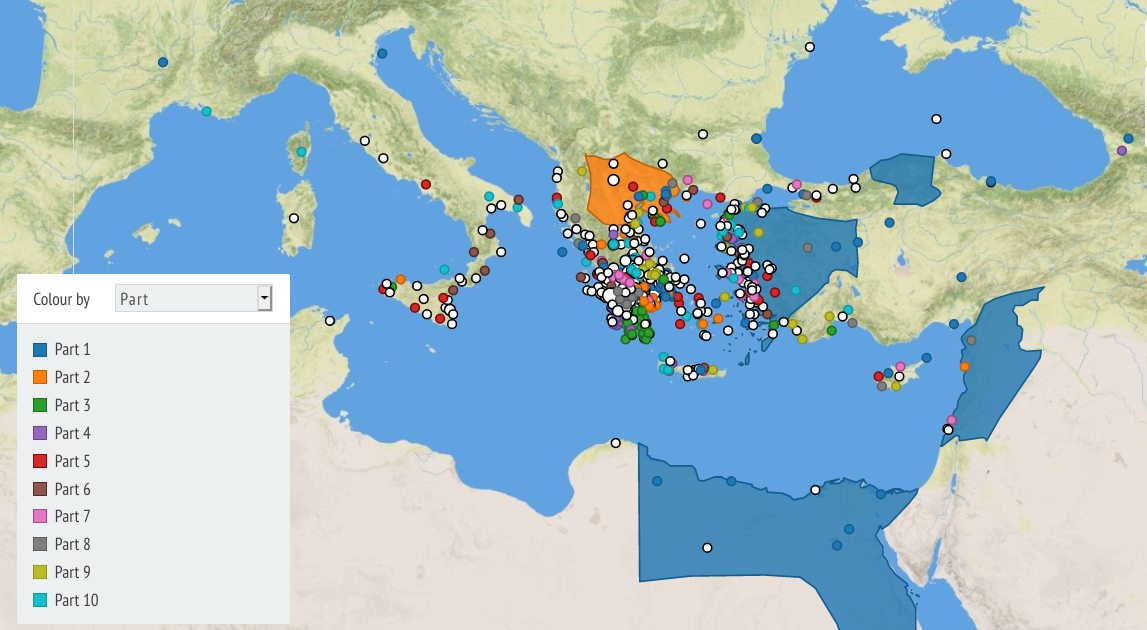

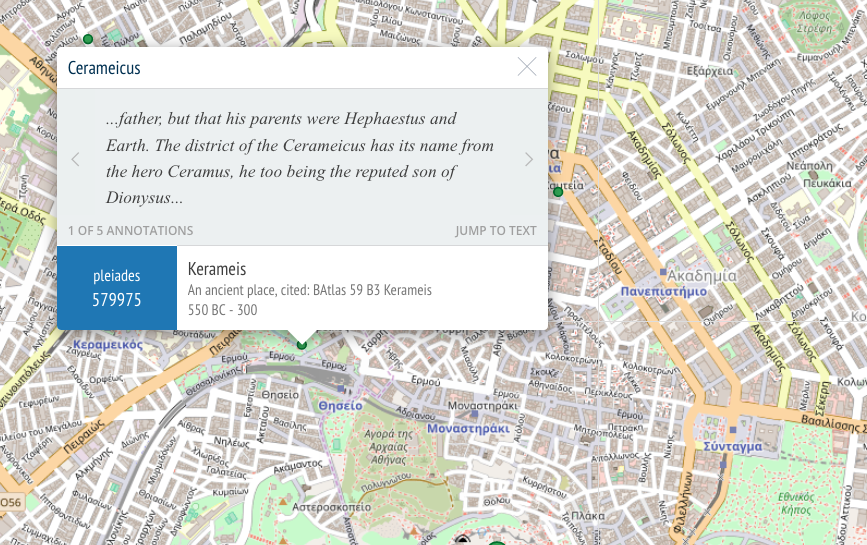

Annotating the Digital Periegesis we are able to examine both distant reading, i.e. broader bird’s-eye horizons (see figure 1), to close reading, ground-up, localised points of view (see figure 2) in our analysis of case studies, and to incorporate disparate kinds of data, linked together by common references through semantic annotation. Building upon visualization technologies for the humanities, we hope to be able to switch between close and distant reading, facilitate individual movements through complex data, and build more dynamic platforms.

Figure 1: Current annotation of space in all 10 books as shown in Recogito built-in mapping visualization platform.

Figure 2: A closer reading of Cerameicus as shown in Recogito built-in mapping visualization platform.

The study of travel literature can be especially informative in relation to space and cultural diversity. In the case of Pausanias, who ‘inhabited an era when the notion of ethnic identity, particularly that of the Greeks, was in a state of ambiguity’.[9]

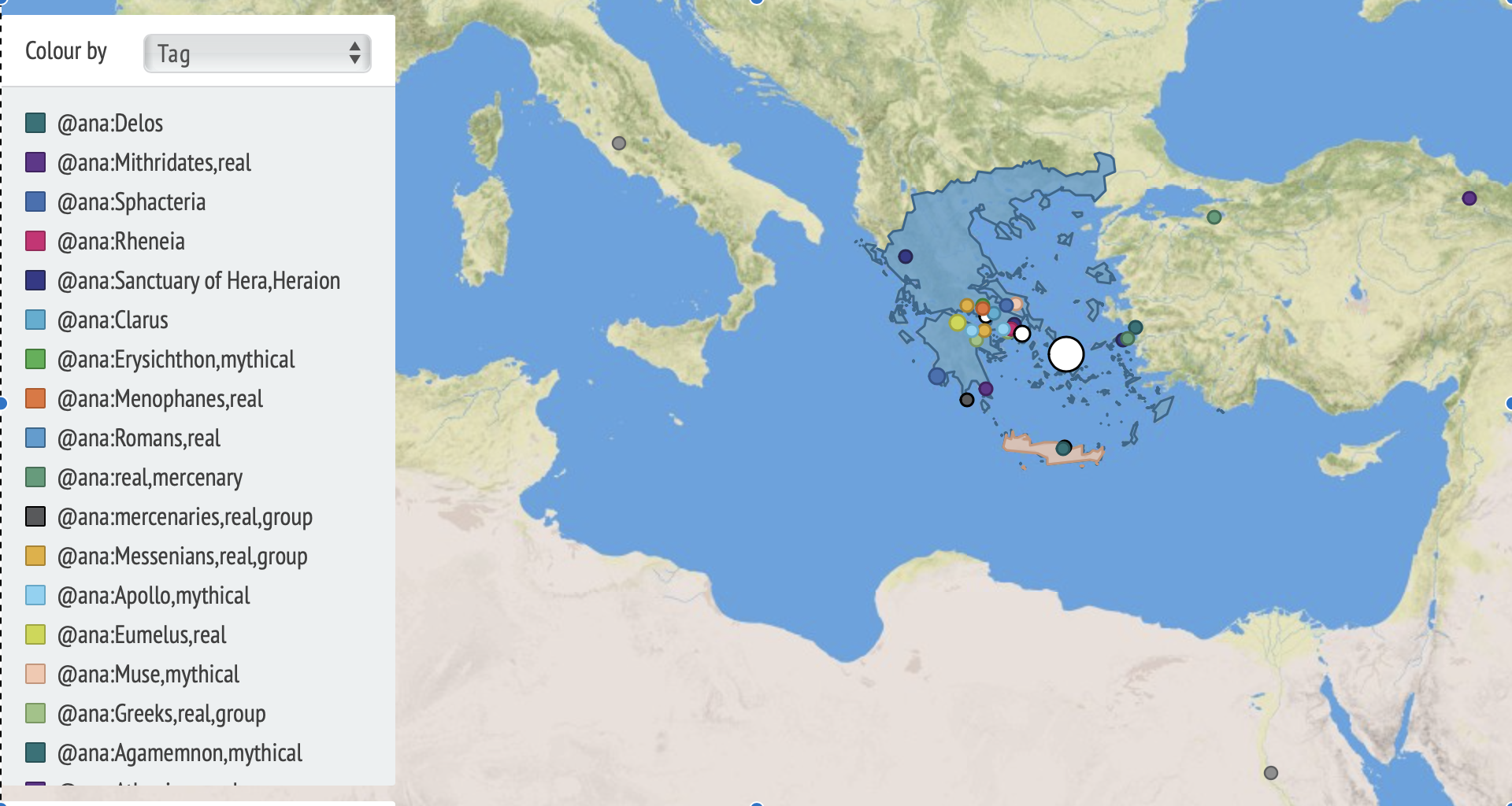

Our thematic case study on Delos provided us with a small visualization of Pausanias’s idealised Hellenic human footprint. The small island below Mykonos has been inhabited since the 3rd millennium BCE. The island was thought to have been inhabited by the piratical Carians[10] and is credited from Homer onward as the birthplace of Apollo. Between 900 BCE and 100 CE, Delos acquired Panhellenic importance as a cult site and was considered a pilgrimage for the Ionians. Home of the Delian League after the Persian wars, Delos becomes a free port during the Roman period. The cultural diversity of the island is evident in its rich archaeological record that includes a temple of Romanised Isis, housing mosaics with the Ugaritic and the world’s oldest Synagogue.

Pausanias does not focus on the island per se. In fact, there are only paragraphs here and there that simply refer to Delos in relation to other places.[11] Instead, the name Delos and its inhabitants (the Delians) are mentioned in relation to other peoples, sites, or artefacts. In Figure 3, Delos’ relation to a number of already geographically verified areas can clearly be seen in a point-mapping environment. Pausanias relates Delos to several people, objects, and places which can be seen in our mapping graph in figure 4. The Recogito platform further enables visualization of free tagging by colour so while we cannot visualize relations just yet, Periegesis refers to important Delian landmarks and artefacts and further relates them to disparate areas in the south-eastern Mediterranean, the majority of which are in Athens. At the time Pausanias wrote Periegesis, Delos was a Roman colony and was gradually turning into a free trading port (166 CE). The visuals that transpire from the text connect the island tightly with Hellenism, first as a Panhellenic site for Apollo in connection to other ritual sites, and later as the heart of the Delian League. Pausanias reports the past as if it were his present: war and conflict, resulting in vandalisms such as burnt cities and missing cult statues. Pausanias’s contemporary perspective establishes his authority as an ever-present witness of Hellenism in the auspices of the Roman Empire.

As such, organising spatial knowledge by annotation and visualising it, brings into critical attention the notion of space and identity. The perception and communication of objective reality in relation to people and space is ‘a form of discourse that can both communicate and problematize concepts of self and “other”, nature and culture, civilization and savagery.’[12] We are currently exploring Pausanias’s iteration of these specific relationships by using the events tab to annotate space.

Figure 3: Verified annotations of places mentioned in relation to Delos as shown in the Recogito built-in mapping visualization platform.

Figure 4: Tagging the properties of space in relation to Delos as shown in the Recogito built-in mapping visualization platform.

Future steps?

Once the text is annotated in Recogito and we have collected a sufficient amount of data, we will import our metadata with digital mapping tools to visualise the Periegesis’s multi-layered spatial configurations, trace the movement (and transformation) of places and peoples and analyse their intersections with different moments in the cultural history of the cultural landscape of Pausanias’s Greece.

This dynamic map interface will incorporate layers of information in order to enable a digital theoria. By visualizing and contemplating, we will then move forward to a deeper interrogation and exploration of diverse data (texts, artefacts, sites, and maps). Specifically, we will address the following research questions:

- How does a study of movement and transformation as a dynamic, geographic visualization diversify our understanding of Hellenic space and its people?

- How do literary constructions of place and space, cultural memory, and present time intersect?

- How can we productively disrupt traditional cartographic representation, so that geographical knowledge can be plotted and explored through action, influence, and memory rather than by topography alone?

- How do we build the literacies for reading such unfamiliar, experimental interfaces?

All of these questions are at the heart of this Digital Periegesis. By organising knowledge and producing metadata that we will then visualise, we hope to create a digital theoria of Pausanias’s Periegesis in GIS, incorporating evidence from the archaeological record of those sites when applicable. We hope that by creating a digital periegesis, we will excite new research questions and inspire other projects to link otherwise disparate data and to problematize digital cartography as visualization, as well as a medium for knowledge production.

Notes

[1] Book 10.7–8.

[2] On theôria see: A. W. Nightingale (2004) “‘Useless’ knowledge: Aristotle's rethinking of theoria,” in Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy: Theoria in its Cultural Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 187–252; E. Hall (2018) Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life, London: Penguin Press: 56.

For a detailed analysis of Aristotle’s definition and use of the term theôria, see D. Roochnik, (January 2009) ‘What is Theoria? Nicomachean Ethics Book 10.7–8’, Classical Philology, Vol. 104, No. 1 pp. 69-82. The University of Chicago Press: 69. Roochnik avoids using the term ‘contemplation’ to describe the act of theôria.

[3] On the concept of cartographic thinking, see Fitzgerald-Johnson 2016.

[4] J. Akujärvi (2012). One and 'I' in the Frame (Narrative). Authorial Voice, Travelling Persona, and Addressee in Pausanias' Periegesis. Classical Quarterly, 62, 327-358. Cambridge University Press: 238; cf. J. E. Cundy (2016) Axion Theas: Wonder, Space, and Place in Pausanias’s Periegesis Hellados, diss. Toronto: Toronto University Press: 14. See also: K. Arafat (1996) Pausanias’ Greece: Ancient Artists and Roman Rulers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.; J. Auberger (1992) ‘Pausanias et les Messenienes: Une histoire d’ amour!’, REA 94: 187-97; J. Auberger (2000) ‘Pausanias et le libre 4Q Une lecon pour l’empire’, Phoenix 54: 255-81; J. Akujärvi (2005) Researcher, Traveller, Narrator: Studies in Pausanias’ Periegesis. Studia graeca et latina lundensia 12. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.; C. Habicht (1998) Pausanias’ Guide to Ancient Greece. 2d ed. Sather Classical Lectures 50. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[5] On space, landscape and “cognitive mapping”: S. Alcock, J. Cherry, and J. Elsner, eds. (2001) Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press; C.f. W. E. Hutton (2005) Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the Periegesis of Pausanias. Greek Culture in the Roman World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press: 4-7.

[6] Perseus CTS TEI texts from the Scaife Library: https://scaife.perseus.org/library/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0525.tlg001.perseus-eng2/

https://scaife.perseus.org/reader/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0525.tlg001.perseus-grc2

[7] E. T. E. Barker, S. Bouzarovski, C.B.R. Pelling, and L. Isaksen (2010): ‘Mapping an ancient historian in a digital age: the Herodotus Encoded Space-Text-Image Archive (HESTIA)’. Leeds International Classical Journal.

[8] R. Simon, L. Isaksen, E. Barker, and P. de Soto Cañamares (2016): The Pleiades gazetteer and the Pelagios project. In: M. Berman, R. Mostern H. Southall, eds. Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers, Indiana: 97-109. R. Simon, E. Barker, L. Isaksen, and P. de Soto Cañamares, P. (2017). Linked Data Annotation Without the Pointy Brackets: Introducing Recogito 2. Journal of Map & Geography Libraries. Volume 13, Issue 1, 2017-05-11: 111-132. R. Simon, E. Barker, L. Isaksen and P. de Soto Can ̃Amares (2015). ‘Linking early geospatial documents, one place at a time: annotation of geographic documents with Recogito’. e-Perimetron, 10(2): 49–59.

[9] On space, landscape and “cognitive mapping”: Alcock et al. 2001; C.f. Hutton 2005 4-7.

[10] Thuc. 1.8.

[11] For an exploration of Delos we uploaded and annotated the following passages in Greek (plain text):

1.18.5 πλησίον δὲ ᾠκοδόμητο ναὸς Εἰλειθυίας, ἣν ἐλθοῦσαν ἐξ Ὑπερβορέων ἐς Δῆλον γενέσθαι βοηθὸν ταῖς Λητοῦς ὠδῖσι, τοὺς δὲ ἄλλους παρ᾽ αὐτῶν φασι τῆς Εἰλειθυίας μαθεῖν τὸ ὄνομα: καὶ θύουσί τε Εἰλειθυίᾳ Δήλιοι καὶ ὕμνον ᾁδουσιν Ὠλῆνος. Κρῆτες δὲ χώρας τῆς Κνωσσίας ἐν Ἀμνισῷ γενέσθαι νομίζουσιν Εἰλείθυιαν καὶ παῖδα Ἥρας εἶναι: μόνοις δὲ Ἀθηναίοις τῆς Εἰλειθυίας κεκάλυπται τὰ ξόανα ἐς ἄκρους τοὺς πόδας. τὰ μὲν δὴ δύο εἶναι Κρητικὰ καὶ Φαίδρας ἀναθήματα ἔλεγον αἱ γυναῖκες, τὸ δὲ ἀρχαιότατον Ἐρυσίχθονα ἐκ Δήλου κομίσαι.

1.29.1 τοῦ δὲ Ἀρείου πάγου πλησίον δείκνυται ναῦς ποιηθεῖσα ἐς τὴν τῶν Παναθηναίων πομπήν. καὶ ταύτην μὲν ἤδη πού τις ὑπερεβάλετο: τὸ δὲ ἐν Δήλῳ πλοῖον οὐδένα πω νικήσαντα οἶδα, καθῆκον ἐς ἐννέα ἐρέτας ἀπὸ τῶν καταστρωμάτων.

1.31.2 ἐν δὲ Πρασιεῦσιν Ἀπόλλωνός ἐστι ναός: ἐνταῦθα τὰς Ὑπερβορέων ἀπαρχὰς ἰέναι λέγεται, παραδιδόναι δὲ αὐτὰς Ὑπερβορέους μὲν Ἀριμασποῖς, Ἀριμασποὺς δ᾽ Ἰσσηδόσι, παρὰ δὲ τούτων Σκύθας ἐς Σινώπην κομίζειν, ἐντεῦθεν δὲ φέρεσθαι διὰ Ἑλλήνων ἐς Πρασιάς, Ἀθηναίους δὲ εἶναι τοὺς ἐς Δῆλον ἄγοντας: τὰς δὲ ἀπαρχὰς κεκρύφθαι μὲνἐν καλάμῃ πυρῶν, γινώσκεσθαι δὲ ὑπ᾽ οὐδένων. ἔστι δὲ μνῆμα ἐπὶ Πρασιαῖς Ἐρυσίχθονος, ὡς ἐκομίζετο ὀπίσω μετὰ τὴν θεωρίαν ἐκ Δήλου, γενομένης οἱ κατὰ τὸν πλοῦν τῆς τελευτῆς.

2.27.1 τὸ δὲ ἱερὸν ἄλσος τοῦ Ἀσκληπιοῦ περιέχουσιν ὅροι πανταχόθεν: οὐδὲ ἀποθνήσκουσιν ἄνθρωποι οὐδὲ τίκτουσιν αἱ γυναῖκές σφισιν ἐντὸς τοῦ περιβόλου, καθὰ καὶ ἐπὶ Δήλῳ τῇ νήσῳ τὸν αὐτὸν νόμον. τὰ δὲ θυόμενα, ἤν τέ τις Ἐπιδαυρίων αὐτῶν ἤν τε ξένος ὁ θύων ᾖ, καταναλίσκουσιν ἐντὸς τῶν ὅρων: τὸ δὲ αὐτὸ γινόμενον οἶδα καὶ ἐν Τιτάνῃ.

2.32.2 τούτου δὲ ἐντὸς τοῦ περιβόλου ναός ἐστιν Ἀπόλλωνος Ἐπιβατηρίου, Διομήδους ἀνάθημα ἐκφυγόντος τὸν χειμῶνα ὃς τοῖς Ἕλλησιν ἐπεγένετο ἀπὸ Ἰλίου κομιζομένοις: καὶ τὸν ἀγῶνα τῶν Πυθίων Διομήδην πρῶτον θεῖναί φασι τῷ Ἀπόλλωνι. ἐς δὲ τὴν Δαμίαν καὶ Αὐξησίαν—καὶ γὰρ Τροιζηνίοις μέτεστιν αὐτῶν—οὐ τὸν αὐτὸν λέγουσιν ὃν Ἐπιδαύριοι καὶ Αἰγινῆται λόγον, ἀλλὰ ἀφικέσθαι παρθένους ἐκ Κρήτης: στασιασάντων δὲὁμοίως τῶν ἐν τῇ πόλει ἁπάντων καὶ ταύτας φασὶν ὑπὸ τῶν ἀντιστασιωτῶν καταλευσθῆναι, καὶ ἑορτὴν ἄγουσί σφισι Λιθοβόλια ὀνομάζοντες.

3.23.3-5 τὸ γὰρ τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος ξόανον, ὃ νῦν ἐστιν ἐνταῦθα, ἐν Δήλῳ ποτὲ ἵδρυτο. τῆς γὰρ Δήλου τότε ἐμπορίου τοῖς Ἕλλησιν οὔσης καὶ ἄδειαν τοῖς ἐργαζομένοις διὰ τὸν θεὸν δοκούσης παρέχειν, Μηνοφάνης Μιθριδάτου στρατηγὸς εἴτε αὐτὸς ὑπερφρονήσας εἴτε καὶ ὑπὸ Μιθριδάτου προστεταγμένον —ἀνθρώπῳ γὰρ ἀφορῶντι ἐς κέρδος τὰ θεῖα ὕστεραλημμάτων—, οὗτος οὖν ὁ Μηνοφάνης, ἅτε οὔσης (4)- ἀτειχίστου τῆς Δήλου καὶ ὅπλα οὐ κεκτημένων τῶν ἀνδρῶν, τριήρεσιν ἐσπλεύσας ἐφόνευσε μὲν τοὺς ἐπιδημοῦντας τῶν ξένων, ἐφόνευσε δὲ αὐτοὺς τοὺς Δηλίους: κατασύρας δὲ πολλὰ μὲν ἐμπόρων χρήματα, πάντα δὲ τὰ ἀναθήματα, προσ εξανδραποδισάμενος δὲ καὶ γυναῖκας καὶ τέκνα, καὶ αὐτὴν ἐς ἔδαφος κατέβαλε τὴν Δῆλον. ἅτε δὲ πορθουμένης τε καὶ ἁρπαζομένης, τῶν τις βαρβάρων ὑπὸ ὕβρεως τὸ ξόανον τοῦτο ἀπέρριψεν ἐς τὴν θάλασσαν: ὑπολαβὼν δὲ ὁ κλύδων ἐνταῦθα τῆς Βοιατῶν ἀπήνεγκε, καὶ τὸ χωρίον διὰ τοῦτο Ἐπιδήλιον ὀνομάζουσι. (5) τὸ μέντοι μήνιμα τὸ ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ διέφυγεν οὔτε Μηνοφάνης οὔτε αὐτὸς Μιθριδάτης: ἀλλὰ Μηνοφάνην μὲν παραυτίκα, ὡς ἀνήγετο ἐρημώσας τὴν Δῆλον, λοχήσαντες ναυσὶν οἱ διαπεφευγότες τῶν ἐμπόρων καταδύουσι, Μιθριδάτην δὲ ὕστερον τούτων ἠνάγκασεν ὁ θεὸς αὐτόχειρα αὑτοῦ καταστῆναι, τῆς τε ἀρχῆς οἱ καθῃρημένης καὶ ἐλαυνόμενον πανταχόθεν ὑπὸ Ῥωμαίων: εἰσὶ δὲ οἵφασιν αὐτὸν παρά του τῶν μισθοφόρων θάνατον βίαιον ἐν μέρει χάριτος εὕρασθαι.

4.4.1 ἐπὶ δὲ Φίντα τοῦ Συβότα πρῶτον Μεσσήνιοι τότε τῷ Ἀπόλλωνι ἐς Δῆλον θυσίαν καὶ ἀνδρῶν χορὸν ἀποστέλλουσι: τὸ δέ σφισιν ᾆσμα προσόδιον ἐς τὸν θεὸν ἐδίδαξεν Εὔμηλος, εἶναί τε ὡς ἀληθῶς Εὐμήλου νομίζεται μόνα τὰ ἔπη ταῦτα. ἐγένετο δὲ καὶ πρὸς Λακεδαιμονίους ἐπὶ τῆς Φίντα βασιλείας διαφορὰ πρῶτον, ἀπὸ αἰτίας ἀμφισβητουμένης μὲν καὶ ταύτης, γενέσθαι δὲοὕτω λεγομένης.

4.33.2 τὸ δὲ ἄγαλμα τοῦ Διὸς Ἀγελάδα μέν ἐστιν ἔργον, ἐποιήθη δὲ ἐξ ἀρχῆς τοῖς οἰκήσασιν ἐν Ναυπάκτῳ Μεσσηνίων: ἱερεὺς δὲ αἱρετὸς κατὰ ἔτος ἕκαστον ἔχει δὲ τὸ ἄγαλμα ἐπὶ τῆς οἰκίας. ἄγουσι δὲ καὶ ἑορτὴν ἐπέτειον Ἰθωμαῖα, τὸ δὲ ἀρχαῖον καὶ ἀγῶνα ἐτίθεσαν μουσικῆς: τεκμαίρεσθαι δ᾽ἔστιν ἄλλοις τε καὶ Εὐμήλου τοῖς ἔπεσιν, ἐποίησε γοῦν καὶ τάδε ἐν τῷ προσοδίῳ τῷ ἐς Δῆλον: “τῷ γὰρ Ἰθωμάτα καταθύμιος ἔπλετο μοῖσα ἁ καθαρὰν κιθάραν καὶ ἐλεύθερα σάμβαλ᾽ ἔχοισα.” Eumelus, οὐκοῦν ποιῆσαί μοι δοκεῖ τὰ ἔπη καὶ μουσικῆς ἀγῶνα ἐπιστάμενος τιθέντας.

4.36.6 τοῦ λιμένος δὲ ἡ Σφακτηρία νῆσος προβέβληται, καθάπερ τοῦ ὅρμου τοῦΔηλίων ἡ Ῥήνεια: ἐοίκασι δὲ αἱ ἀνθρώπειαι τύχαι καὶ χωρία τέως ἄγνωστα ἐς δόξαν προῆχθαι. Καφηρέως τε γάρ ἐστιν ὄνομα τοῦ ἐν Εὐβοίᾳ τοῖς σὺν Ἀγαμέμνονι Ἕλλησιν ἐπιγενομένου χειμῶνος ἐνταῦθα, ὡς ἐκομίζοντο ἐξ Ἰλίου: Ψυττάλειάν τε τὴν ἐπὶ Σαλαμῖνι ἴσμεν ἀπολομένων ἐναὐτῇ τῶν Μήδων. ὡσαύτως δὲ καὶ τὴν Σφακτηρίαν τὸ ἀτύχημα τὸ Λακεδαιμονίων γνώριμον τοῖς πᾶσιν ἐποίησεν: Ἀθηναῖοι δὲ καὶ Νίκης ἀνέθηκαν ἄγαλμα ἐν ἀκροπόλει χαλκοῦν ἐς μνήμην τῶν ἐν τῇ Σφακτηρίᾳ.

5.7.8 πρῶτος μὲν ἐν ὕμνῳ τῷ ἐς Ἀχαιίαν ἐποίησεν Ὠλὴν Λύκιος ἀφικέσθαι τὴν Ἀχαιίαν ἐς Δῆλον ἐκ τῶν Ὑπερβορέων τούτων: ἔπειτα δὲ ᾠδὴν Μελάνωπος Κυμαῖος ἐς Ὦπιν καὶ Ἑκαέργην ᾖσεν, ὡς ἐκ τῶν Ὑπερβορέων καὶ αὗται πρότερον ἔτι τῆς Ἀχαιίας ἀφίκοντο καὶ ἐς Δῆλον.

5.19.10 τὸν μὲν δὴ τὴν λάρνακα κατεἰργασμένον ὅστις ἦν, οὐδαμῶς ἡμῖν δυνατὰ ἦν συμβαλέσθαι: τὰ ἐπιγράμματα δὲ τὰ ἐπ᾽ αὐτῆς τάχα μέν που καὶ ἄλλος τις ἂν εἴη πεποιηκώς, τῆς δὲ ὑπονοίας τὸ πολὺ ἐς Εὔμηλον τὸν Κορίνθιον εἶχενἡμῖν, ἄλλων τε ἕνεκα καὶ τοῦ προσοδίου μάλιστα ὃ ἐποίησεν ἐς Δῆλον.

8.23.5 εἰ δὲ Ἑλλήνων τοῖς λόγοις ἑπόμενον καταριθμήσασθαι δεῖ με ὁπόσα δένδρα σῶα ἔτι καὶ τεθηλότα λείπεται, πρεσβύτατον μὲν ἡ λύγος ἐστὶν αὐτῶν ἡ ἐν τῷ Σαμίων πεφυκυῖα ἱερῷ Ἥρας, μετὰ δὲ αὐτὴν ἡ ἐν Δωδώνῃ δρῦς καὶ ἐλαία τε ἡ ἐν ἀκροπόλει καὶ ἡ παρὰ Δηλίοις: τρίτα δὲ ἕνεκα ἀρχαιότητος νέμοιεν ἂν τῇ δάφνῃ τῇ παρὰ σφίσιν οἱ Σύροι: τῶν δὲ ἄλλων ἡ πλάτανός ἐστιν αὕτη παλαιότατον.

8.33.2 Μυκῆναι μέν γε, τοῦ πρὸς Ἰλίῳ πολέμου τοῖς Ἕλλησιν ἡγησαμένη, καὶ Νῖνος, ἔνθα ἦν Ἀσσυρίοις βασίλεια, καὶ Βοιώτιαι Θῆβαι προστῆναι τοῦ Ἑλληνικοῦ ποτε ἀξιωθεῖσαι, αἱ μὲν ἠρήμωνται πανώλεθροι, τὸ δὲ ὄνομα τῶν Θηβῶν ἐς ἀκρόπολιν μόνην καὶ οἰκήτορας καταβέβηκεν οὐ πολλούς. τὰ δὲ ὑπερηρκότα πλούτῳ τὸ ἀρχαῖον, Θῆβαί τε αἱ Αἰγύπτιοι καὶ ὁ Μινύης Ὀρχομενὸς καὶ ἡ Δῆλος τὸ κοινὸν Ἑλλήνων ἐμπόριον, αἱ μὲν ἀνδρὸς ἰδιώτου μέσου δυνάμει χρημάτων καταδέουσιν ἐς εὐδαιμονίαν, ἡ Δῆλος δέ, ἀφελόντι τοὺς ἀφικνουμένους παρ᾽ Ἀθηναίων ἐς τοῦ ἱεροῦ τὴν φρουράν, Δηλίων γε ἕνεκα ἔρημός ἐστιν ἀνθρώπων.

8.48.3 ἐνομίσθη δὲ ἐπὶ τοιῷδε: Θησέα ἀνακομιζόμενον ἐκ Κρήτης φασὶν ἐν Δήλῳ ἀγῶνα ποιήσασθαι τῷ Ἀπόλλωνι, στεφανοῦν δὲ αὐτὸν τοὺς νικῶντας τῷ φοίνικι. τοῦτο μὲν δὴ ἄρξαι λέγουσιν ἐντεῦθεν: τοῦδὲ φοίνικος τοῦ ἐν Δήλῳ μνήμην ἐποιήσατο καὶ Ὅμηρος ἐν Ὀδυσσέως ἱκεσίᾳ πρὸς τὴν Ἀλκίνου θυγατέρα.

9.34.6 τοῦ δὲ ὄρους τοῦ Λαφυστίου πέραν ἐστὶν Ὀρχομενός, εἴ τις Ἕλλησιν ἄλλη πόλις ἐπιφανὴς καὶ αὕτη ἐς δόξαν. εὐδαιμονίας δέ ποτε ἐπὶ μέγιστον προαχθεῖσαν ἔμελλεν ἄρα ὑποδέξεσθαι τέλος καὶ ταύτην οὐ πολύ τι ἀποδέον ἢ Μυκήνας τε καὶ Δῆλον. περὶ δὲ τῶν ἀρχαίων τοιαῦτ᾽ ἦν ὁπόσα καὶ μνημονεύουσιν. Ἀνδρέα πρῶτον ἐνταῦθα Πηνειοῦ παῖδα τοῦ ποταμοῦ λέγουσιν ἐποικῆσαι καὶ ἀπὸτούτου τὴν γῆν Ἀνδρηίδα ὀνομασθῆναι:

9.40.3 Δαιδάλου δὲ τῶν ἔργων δύο μὲν ταῦτά ἐστιν ἐν Βοιωτοῖς, Ἡρακλῆς τε ἐν Θήβαις καὶ παρὰ Λεβαδεῦσιν ὁ Τροφώνιος, τοσαῦτα δὲ ἕτερα ξόανα ἐν Κρήτῃ, Βριτόμαρτις ἐν Ὀλοῦντι καὶ Ἀθηνᾶ παρὰ Κνωσσίοις: παρὰ τούτοις δὲ καὶ ὁ τῆς Ἀριάδνης χορός, οὗ καὶ Ὅμηρος ἐν Ἰλιάδι μνήμην ἐποιήσατο, ἐπειργασμένος ἐστὶν ἐπὶ λευκοῦ λίθου. καὶ Δηλίοις Ἀφροδίτης ἐστὶν οὐ μέγα ξόανον, λελυμασμένον τὴν δεξιὰν χεῖρα ὑπὸ τοῦ χρόνου: κάτεισι δὲ ἀντὶ ποδῶνἐς τετράγωνον σχῆμα.

10.12.5 τὴν δὲ Ἡροφίλην οἱ ἐν τῇ Ἀλεξανδρείᾳ ταύτῃ νεωκόρον τε τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος γενέσθαι τοῦ Σμινθέως καὶ ἐπὶ τῷ ὀνείρατι τῷ Ἑκάβης χρῆσαί φασιν αὐτὴν ἃ δὴ καὶ ἐπιτελεσθέντα ἴσμεν. αὕτη ἡ Σίβυλλα ᾤκησεμὲν τὸ πολὺ τοῦ βίου ἐν Σάμῳ, ἀφίκετο δὲ καὶ ἐς Κλάρον τὴν Κολοφωνίων καὶ ἐς Δῆλόν τε καὶ ἐς Δελφούς: ὁπότε δὲ ἀφίκοιτο, ἐπὶ ταύτης ἱσταμένη τῆς πέτρας ᾖδε.

[12] Hutton 2005: 4-16.

About the authors:

Anna Foka

Scientific Leader, DH Uppsala,

Department of Archives, Museums and Libraries

Faculty of Arts and Humanities

Uppsala University

anna.foka@abm.uu.se | @fencingfox

https://katalog.uu.se/profile/?id=N18-926

Associate Professor in Information Technology and Humanities

Humlab, Umeå University

Elton Barker

Reader in Classical Studies

School of Arts & Cultures

Faculty of Arts & Humanities

The Open University’

elton.barker@open.ac.uk | @eltonteb

http://www.open.ac.uk/people/eteb2

Community Director, Pelagios

http://commons.pelagios.org/ | @Pelagiosproject

Kyriaki Konstantinidou

Umeå universitet

Senior Research Assistant at HumLab

https://www.umu.se/en/staff/kyriaki-konstantinidou/

Johan Åhlfeldt

Research Engineer

Centrum för digital humaniora

Institutionen för litteratur, idéhistoria och religion

Göteborgs universitet