BLOG Virtues, Vices, and Vectors: Digital Tools and the Study of Medieval Sermons

by Inka Moilanen, Department of History, Stockholm University

Digital texts as historical sources

With the increase of digitized historical texts, databases with user-friendly search functions, and digital projects (or TRCs, Thematic Research Collections) with a mixture of research tools and a variety of archival material, the possibilities for historians have multiplied. That so many medieval texts have been transferred into digital formats in the past few years is an obvious advantage for medieval studies. Everyone is grateful that we can now find critical editions and high-resolution manuscript images straight from our own computer screens, and do the time-consuming research right at home, instead of travelling to different libraries and archives across the world. Not only can we now download a text and do the traditional close reading (often) for free, but we can now also manipulate the data that would have been near impossible with printed texts. This is what brings us to using digital databases as tools in the study of medieval sermons – not just as a deposit for texts in an electronic format.

The digitized text itself allows for a re-evaluation of how we pose our research questions and calls for a critical discussion of the nature of our sources and the knowledge we gain from them. Although the process of making medieval texts available in a digital format is not complete (will it ever be?), [1] great accomplishments have been achieved in recent times that have made it possible to shift from the phase of reassembling and collation to one where scholars can use this new material in analyses that differ from ‘traditional’ methods of close-reading. In this respect, the methods that have been developed within Digital Humanities (reaching back to 1960s humanities computing, with its roots in the late 1940s) offer new and promising prospects for historians.[2]

A ‘traditional’ historian by training, I have more recently been drawn into using digital methods in my research on medieval sermons. The main attractiveness of practicing digital history, to me, is precisely the possibility of inquiring into the nature of knowledge, the transmission of texts, and the critical evaluation of historical texts in a new format. But most of all, I am intrigued by the opportunities that a digital text can offer a scholar that an analogue text cannot. In my research project that is currently ongoing, I implement computational methods in the study of digitized text corpora, focusing on identifying and analysing changes in the social-religious climate prior to the drastic increase of popular (and ‘heretical’) social movements in the High Middle Ages. One of the most important aims is, specifically, to test and determine the usefulness of computational methods in the study of medieval textual culture. In this respect, the medieval notions of virtues and vices coincide with digital tools in a vector space (more about vectors below).

Some of the prerequisites that a study like this must have include a massive amount of work done by other scholars. The texts that were originally written on parchment by hand must already be edited to a modern typescript and transferred into a digital format in large databases. Databases, however, also unavoidably restrict the research questions that can be posed. At least, scholars who endeavour to use this material should think carefully about the foundations upon which the database is built.[3] If we are to overcome these problems, we need to re-edit the thousands of texts that occur in older editions, not to speak of all the different versions and adaptations in the medieval manuscripts themselves, which often derive from a variety of historical contexts.[4] This is not necessarily problematic when dealing with a relatively small corpus when the researcher can personally, or with a team, verify the textual contexts or each source themselves. The situation is more challenging when the historian attempts to enter into the territories of digital analysis that require the extraction, collation, and manipulation of thousands of texts. As the literary scholar Franco Moretti has suggested, one of the benefits of analysing texts on a macro level is that, in this way, it should be possible to avoid the tendency of focussing on the significance of the established literary canon, thus shedding more light on the less studied and anonymous texts, which have not piqued the interest of modern scholars as much as the ‘great names’.[5] This is a worthy goal when the objective is to gain understanding of the workings of sermons and preaching in the social life of the medieval period. But in order to get meaningful results by means of “distant reading” (a term coined by Moretti),[6] a large corpus is required - larger than would be possible to analyse with close reading only.

Analysing medieval texts with vector space modelling

The project I am involved in is, in essence, an examination of the uses of digital methods for the study of medieval textual culture. The combination of more ‘traditional’ approaches of conceptual history and close reading with computational tools seems like a worthwhile attempt, not least for the purposes of testing, exploration, and evaluation. The most obvious benefit of using the principles of conceptual history is that they pay particular attention to the use of value-laden concepts as means in the establishment of social order. In addition, using the principles of conceptual history together with digital tools highlights the polysemic nature of concepts as context-dependent, and calls for the examination of concepts – and changes occurring in them – in relation to their surrounding discourses. In order to recognise these relationships, therefore, the researcher must analyse a large set of source material and chart out the surrounding discourses that are associated with utterances about the conceptions of social order, its foundations, and accepted limits.

For the identification of similarities and nearness to other terms, I have decided to test vector space modelling, a digital data indexing and processing tool that has good potential for the analysis of historical data.[7] With the help of vector space modelling it is possible to identify relationships between different conceptual categories that have been associated with certain social negotiations in different historical contexts. These relationships can be seen as “a pattern of word use that establishes networks across language”. [8]

Studies that deal with different historical eras and different source material but use similar methodological tools have been very successful in demonstrating the opportunities many computational approaches have for the analysis of conceptual change. They also offer valuable examples which can be developed further.[9] It should be noted that these endeavours are not an entirely new development in medieval studies. For instance, as early as in 1978, a special issue devoted to ‘Medieval Studies and the Computer’ was published in Computers and the Humanities. The various articles explore a range of issues, from encoding and concording medieval texts, the analysis of metrical patterns of Beowulf, to the study of the educational status of the clergy with the help of quantitative analysis using a set of routines written in the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Language (SAIL).[10]

There are several possibilities for identifying and embedding words and documents that are extracted from digital databases. The Gensim implementation of word2vec is especially useful when creating word-context matrices which can be used in the study of word similarity, based on a window of words of a certain length around the sample word (e.g. error, controversia, discordia, haereticus, but also concordia, emendatio, redemptio, etc.).

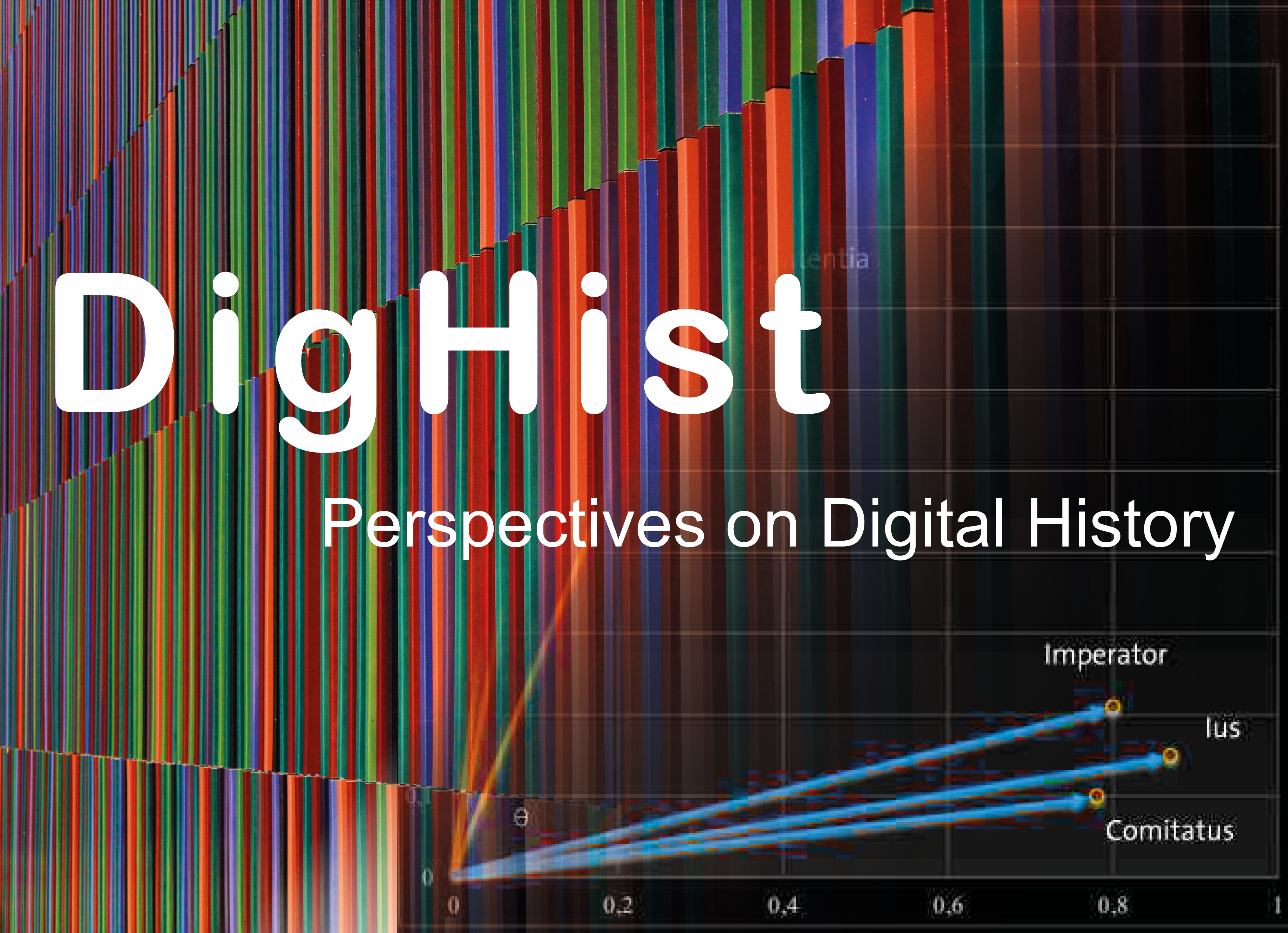

A simple example of the occurrence of six words in six documents. Words relating to morality and sinfulness (repentance, pride, humility) are more present in sermon literature than in legislative texts, which use a largely different vocabulary (emperor, company/retinue [of soldiers], justice).

The foundation rests on a distributional hypothesis that words that occur in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. This premise is notably valuable for the study of medieval sermons and other normative texts that deal with virtues and vices.

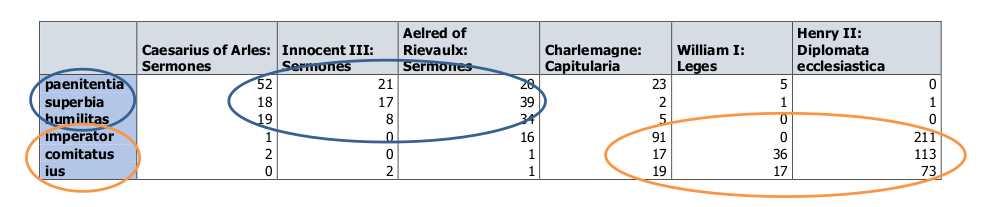

When aiming to identify the similarity between different texts, and not just words, doc2Vec comes into picture. It is based on word2vec algorithm and can be used to embed paragraphs and documents with labels. In both word-context and term-document matrices each document or word is represented as a point in space.

The relationship between words in a given textual corpus is more distant the farther away the points appear in a vector space. The position of each point can be determined with the help of cosine similarity.

Both word-context and term-document matrices build upon the notion that points that are close together (in the vector space) are semantically similar, and those that are far apart are semantically distant. This is especially helpful in the identification of relationships between different conceptual categories that were associated with each other in different historical contexts. These relationships can then be explored and visualized with the help of graphs or networks (for which there are other useful open source programs, such as Gephi) that present these associations as a structure in which the interconnected elements, in this case words and documents, are tied to each other. These relationships may be merely definitional, but also assertional or implicational, meaning that the relationship carries along beliefs, assumptions, and value-judgments, as well as expectations of causality.[11] This is when the historian gets to take off their digital hat and get to work with the fundamentals of our discipline: interpretation, explanation, and the critical evaluation of the past.

The many layers of text and the digital database

Getting back to the issues of source texts and digital databases, in this final part I wish to briefly reflect upon the more problematic aspects of source criticism that may arise when a researcher has to deal with distant reading and extraction of research data from large digitized corpora. One of the benefits of broader statistical or macro-analytical interpretations of historical source material is that the computer can handle much more data than a single scholar can. This advantage can, however, also turn out to be a drawback, or at least a challenge, that requires careful methodological reflection.

As mentioned before, in order to be able to effectively use digital methods such as vector space modelling in a macro-level analysis of semantic developments, a large corpus is required. In turn, certain preconditions need to already be in effect. First, the texts that originally were written on parchment must already be edited (either in print or in a digital format. If in print, they must be transferred to a digital format, manually or by OCR). Second, edited texts should already have been collated in a database. The source texts that we study by means of digital databases are thus twice (or more) removed from their original context.

Many TRCs build upon original research of medieval manuscripts, but there are also databases that, by comparison, are based on older, printed editions of medieval texts (not always critical). In the earlier stages of digitalization, the large collections of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries often formed the basis upon which databases were built. As useful as the huge collections are, there may arise serious source critical issues when they are used as a foundation for a database that is then used for the purposes of digital history with computational methods, especially if links to original manuscript sources are missing.

For an uncritical user, digital databases may even create an illusion of completeness. By this I mean that when collated into a large database, the digitized format itself may give the impression of a ‘whole corpus’ in a modern appearance, ready to be grabbed and used by the digital natives of the twenty-first century. If not well-documented and traceable to original medieval manuscripts, digital databases may adumbrate the stages of selection, omission, and edition, omitting the details. It is useful to bear in mind that all corpora, despite the format, are always restricted and dependent on the survival of material remains (be that texts, objects, images, etc.).

I am not, at any rate, claiming that this is a problem all digital databases have, as there are several outstanding examples of databases that retain the documentation and links to original sources.[12] There are also extremely useful and invaluable databases that I use in my own project, particularly the superb Computational Historical Semantics built by Goethe University and Text Technology Lab, Frankfurt am Main, with tools for semantical analysis of Latin texts, fully lemmatized so that it takes into account all the inflected forms and spelling variations of each Latin word. It collates texts from multiple platforms, including Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Classiques de l’histoire au Moyen Âge, Central European Medieval Texts, Corpus Corporum, and Institut de recherche et d’histoire des textes. That some of the texts derive from, for instance, Patrologia Latina (1844–1864), and that “there are OCR mistakes”, as cautioned by the Corpus Corporum site, however, will necessarily alert the historian to think about the many layers of textual transmission, as any erroneous data that has been transferred into a new format may have consequences for the results.

Is medieval parchment then more ‘real’ as a historical source than a medieval text in a digital database? How about an edited text printed on paper? In both cases the text is a result of transcription, accompanied with decisions, selections, and omissions. How should we take into account the characteristics of textual transmission, copying, and adaptation in the Middle Ages, when the notion of the ‘text’ was more malleable and flexible than what it is today? It is a challenge to consider the various manuscript contexts and later uses of texts in our research if we rely on databases that do not implement documentation to all the different versions of a text.

Despite these cautionary reflections, I remain positive for the possibilities of digital history. Digitalization of large amounts of historical texts has opened up new ways to pose research questions and to employ new methods, which would not have been possible before. In the end, when we have extracted and organized our data from digital databases which then has been manipulated and analysed with digital tools, the information that we create must always be interpreted by humans. Data that we get from implementing vector space modelling is not knowledge; it has to be interpreted by researchers in order to be meaningful. This possibility of interpretation is one of the benefits of many digital methods in history, not that they replace the ‘traditional’ reading of sources and historical source criticism, or that they would make the research itself faster or easier. On the contrary, data manipulation is often time-consuming and requires as much effort as close reading. Instead, the benefit lies in the capacity of these tools to analyse a much larger amount of material[13] than would ever be possible with only close reading. Together with close reading and manuscript studies, the practice of digital history enables the scholar to venture into new territories and take on intriguing challenges. That is, as long as we remember, at the same time, to reflect upon the many layers of textual transmission and the birth of our sources, not just in historical times but also in our own.

References

[1] The number of medieval manuscripts is not the only issue. The nature of medieval textual culture itself poses challenges to a modern editor. In addition, reproducing a medieval text in a digital format can mean different things, such as imaging a manuscript, transforming a handwritten text into a digital one with recognizable characters, or, for instance, encoding a text with TEI elements. Each of these processes include a careful consideration of the nature of the medieval text. For a useful overview, see: Creating a Digital Scholarly Edition with the Text Encoding Initiative: A Textbook for Digital Humanists, ed. by Marjorie Burghart (DEMM, 2017). At https://www.digitalmanuscripts.eu/digital-editing-of-medieval-texts-a-textbook/, accessed January 14, 2019.

[2] The pioneer of humanities computing is considered to be Roberto Busa, SJ, who, in 1949, started his work with Index Thomisticus, a massive lemmatized concordance to the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. The project was funded by IBM and published in the 1970s. See Roberto Busa, ‘The Annals of Humanities Computing: The Index Thomisticus’, Computers and the Humanities, 14:2 (1980), pp. 83–90.

[3] For a good introduction on reading digital data, see Research Methods for Reading Digital Data in the Digital Humanities, ed. by Gabriele Griffin and Matt Hayler (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

[4] As everyone knows, editing a medieval text is a painstakingly laborious and time-consuming task, which might not be even lucrative, if you think of your future prospects of obtaining financing. Unfortunately, quick results are expected to get funding in today’s academia, and the number of publications weighs heaviest in the Odyssey towards tenure.

[5] Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (London: Verso, 2007).

[6] Franco Moretti, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013).

[7] Dan Jurafsky and James H. Martin, ‘Vector Semantics’, in Speech and Language Processing, 3rd ed. (September 23, 2018). At https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/, accessed January 28, 2019; Ben Schmidt, ‘Vector Space Models for the Digital Humanities’, in Ben’s Bookworm Blog (October 25, 2015). At http://bookworm.benschmidt.org/posts/2015-10-25-Word-Embeddings.html, accessed January 28, 2019.

[8] Michael A. Gavin, ‘The Arithmetic of Concepts: A Response to Peter de Bolla’, in Modeling Literary History (September 18, 2015). At http://modelingliteraryhistory.org/2015/09/18/the-arithmetic-of-concepts-a-response-to-peter-de-bolla/, accessed January 28, 2019.

[9] Peter De Bolla, The Architecture of Concepts: The Historical Formation of Human Rights (New York: Fordham, 2013); Charles W. Romney, ‘Using Vector Space Models to Understand the Circulation of Habeas Corpus in Hawai’i, 1852–92’, Law and History Review 34:4 (2016), pp. 999–1026. See also Gavin 2015.

[10] Anne Gilmour-Bryson, Medieval Studies and the Computer (New York: Pergamon Press, 1979).

[11] John F. Sowa, ‘Semantic Networks’, in Encyclopedia of Artificial Intelligence, ed. by Stuart C. Shapiro, 2nd ed. (Chichester: Wiley, 1992). Updated version at http://www.jfsowa.com/pubs/semnet.htm (2015), accessed January 28, 2019.

[12] For instance, the newly launched Norse World, which will be presented in this blog series on April 5.

[13] Sometimes referred to as ‘big data’, although it is questionable to talk about real ‘big data’ in terms of medieval textual sources.