Countess Judith of Huntington, Earl Waltheof and lived religion

by Elizabeth Dachowski and M. Wendy Hennequin, Tennessee State University

We stumbled onto Earl Waltheof and Countess Judith of Huntington accidentally. We randomly searched the Prosapography of Anglo-Saxon England database for a Domesday Book lesson in our medieval English literature and history class. We don’t even remember exactly what we were searching for, though it was probably a figure or property mentioned in Richard A. Fletcher’s Bloodfeud, which we assigned to our students. We were astonished to see a woman, Countess Judith, come up repeatedly in the results. Who was this woman, we wondered, who held lands and titles in her own right, and why had we never heard of her?

We soon discovered Countess Judith’s history: niece to William the Conqueror, the daughter of his sister Adele and her second husband, Judith married to the last Anglo-Saxon earl, Waltheof, as part of the peace agreement after the northern rebellion against King William in 1069. This Earl Waltheof, we discovered, was part of that feud in Fletcher’s book; he avenged his father Siward upon the sons of Carl. While piecing together Judith’s life, we learned Waltheof’s story: he was born in the last decades of Anglo-Saxon rule of England, the second son of the earl of Bernicia; he not only avenged his father’s life, but was later reputed to kill a hundred men at Hastings. Waltheof was important and well-respected enough for William the Conqueror to take him as hostage after the Conquest, and also influential enough for William to make peace with in 1069. Oh, and Waltheof was apparently executed for treason—and then, to our astonishment, became a local saint.

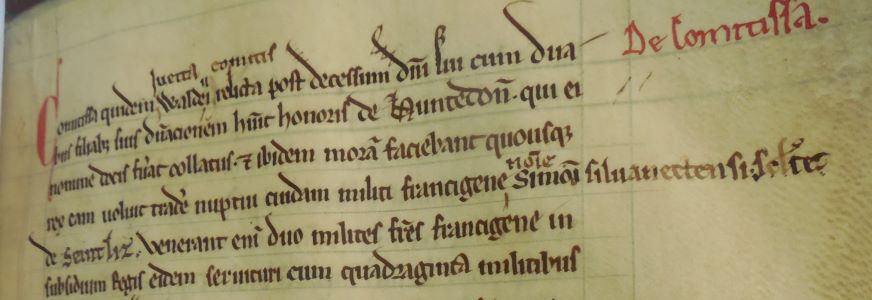

Image 1: Douai BM, Ms 852, f. 64 (used by permission). The initial page of “De Comitissa,” an account of Countess Judith’s life and descendants. Even though she is the subject of the narrative, her name was at first omitted from the first line of text and added just above the line. Note also the rendering of her name as “Juetta,” as she is consistently known in this text.

Two wonderful things about research, especially research into the Middle Ages, are discovering something about your topic and discovering something fascinating but tangential to your topic. One such side issue that we did not have time to follow up on was Waltheof’s mythological paternal descent from a well-known Norwegian bear. Judith, in order to avoid re-marriage, took sanctuary and became “semi-cloistered”; we still haven’t successfully defined the term or determined which king (William or William Rufus) wanted her to remarry. In order to understand Waltheof’s burial in a ditch and subsequent interment at Crowland Abbey, we investigated deviant burials, which led to special features of the burials of witches (or perhaps midwives) and ways to prevent corpses from becoming revenants. Beheadings and decapitations also figured strongly in our research, leading to St. Alban who was beheaded in place of the fictitious St. Amphibalus, a saint created from the mistranslation of “cloak” as a proper name. We researched in circles when we found that an early humanist identified as a son of Waltheof “a certain man” who lived in his father’s tomb and sponsored an unofficial cult at Romsey. Many researchers repeated this conclusion, even though Waltheof was buried at Crowland, had no documented sons, and the primary source quoted by the humanist did not name Waltheof specifically. (Finally, after tracking down the original attribution and deciding it was faulty, we stumbled on an article that did the legwork for us.)

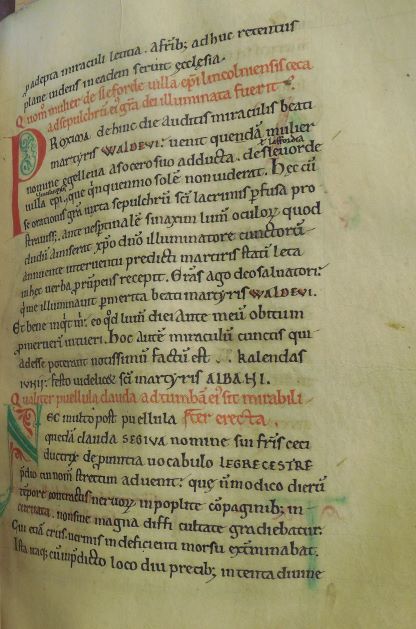

Image 2: Douai BM, Ms 852, f. 68 (used by permission). A page from the miracles of Waltheof. Note the alternating red and green initials marking out the different miracle stories. Waltheof’s name is picked out in red in the body of the text. Note the reference in the last line of the central miracle on this folio to the feast of St. Alban as a date reference.

Our latest tangent has been lived religion. Our research on Waltheof mostly derives from medieval hagiographies and histories, which show evolving interpretations of Waltheof’s life and death in the decades after his burial. We presented a conference paper on Waltheof’s afterlives based on this research, so Scandia’s call for papers on lived religion seemed like a natural progression. The concept of “lived religion” in the context of United States religious history counters the more traditional top-down analysis focused on denominational differences from a very narrow mainline Protestant perspective. These studies therefore often branded Catholic and folk religious practices as “superstition,” separate from theologically sophisticated and elite religious practices. Yet, for decades, medievalists have studied seriously the origins of these so-called "superstitions" as the genuine lived religion of medieval peoples. Medievalists often have many fewer sources than Americanists, and sometimes we lack entire categories of sources, such as the informal writings of working-class people. We thus routinely use our sources to address many questions beyond their original purpose. Writing about Waltheof’s path to sainthood as “lived religion” has allowed us to integrate our work into a scholarly discourse beyond medieval studies and forced us to consider the theoretical implications of the questions we ask of our sources.