Chatty reliquaries and engaged emotions

by Sofia Lahti, Linnaeus University

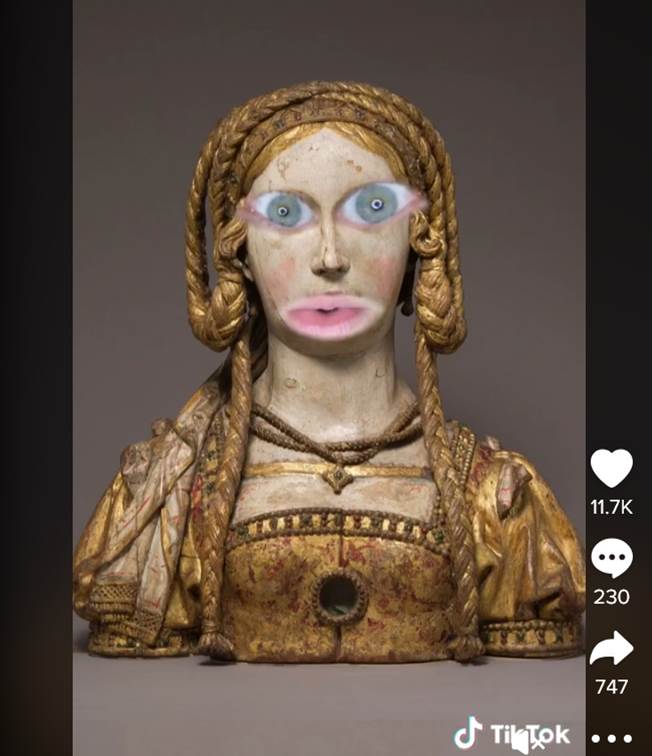

Medieval art has proved to be very meme-able. Few, however, have taken it upon themselves to meme and animate reliquaries. But Greedy Peasant (created by Tyler Gunther) has – and how quirky they are!

My own research has always been focused on medieval reliquaries – those precious ecclesiastical objects in various shapes, sizes and materials, all made to house, protect and represent the relics of saints. In the Nordic churches, like in all Catholic Europe, there were thousands of them during the Middle Ages. Some of them were shaped as busts, with calmly expressive and life-like faces. Busts or heads made of shining gold or silver may have seemed intimidating in a dimly illuminated church, whereas wooden busts, with faces painted to resemble ours, seem kind and approachable, often with a smile on their face. This aspect is reflected in Greedy Peasant’s videos, too: the chatty reliquaries are all painted and nearly realistic wooden busts, whereas other reliquaries, such as arms/hands or monstrances, turn out to be somewhat less communicative.

In Greedy Peasant’s video clips, reliquary busts of Saint Ursula, Saint Balbina, St Bridget and others in the Met Museum’s collection are prone to gossip and bickering. This may not be the way they would have been perceived in the Middle Ages – although who knows? Looking at the wild variety of the drolleries in manuscript margins, nearly anything seems to have occurred to some medieval creative minds. But let’s admit it: we have no written sources on gossiping reliquary busts.

Screenshot from the Greedy Peasant TikTok account from a video posted on 6.4.2021.

While working on my PhD-dissertation, trying to gather information on all the known surviving reliquaries and written mentions of lost reliquaries in the Nordic countries, I became aware of a discordance of sorts. Most of the surviving reliquaries are visually impressive – or have been – with numerous details, precious materials and iconography. They must have been dazzling for the medieval viewers, as they are to us now. So why, in the written sources such as miracle accounts, this visual richness is often described with very few words or not at all?

Bust reliquary in the Church of St Mary, Sigtuna, Sweden. Photo: Sofia Lahti.

Now, working in two projects that operate with the concept of lived religion, I wanted to keep that question in mind while figuring out more about reliquaries’ roles in the religious situations in which they were present. Their message was visual, but did they also speak to the other senses? This is the part we can’t conclude by looking at the remaining reliquaries in museums, on display behind glass. It’s difficult to imagine how they would smell, sound, or move, or how it would feel to touch them or lift them and feel their weight, and simultaneously feel the presence of the numinous. Even Greedy Peasant can’t really help with that.

Luckily, the Nordic written material can actually help with that. Miracle stories, translation reports and chronicles witness that reliquaries were indeed experienced through sound, scent, touch and movement, and that those encounters were emotionally charged. I believe their visual and material appearance – although often omitted in the written reports of those situations – was instrumental for tuning in the other senses to perceiving those phenomena and for engaging the emotions.

After all, the videos of laughing reliquaries do reflect several aspects that can be recognised in what we know about the medieval cultures around holy images and relics. They were perceived as capable of moving, talking, and shedding tears. Images and objects could be perceived as having their distinct characteristics and personalities apart from the saint they represented; for instance, as David Freedberg observes in the Power of Images (1989), the Virgin Mary images of different churches would be known to respond to different prayers or help in different ailments. The emotions around devotional images and relics were not exclusively friendly: there was competition and envy between churches for the possession of more powerful images or relics that attracted more pilgrims. Although perhaps not gossiping or bickering, images or relics – or the saints whose presence was contained in those objects – were also reported to complain about their bad or negligent treatment and require to be moved.

“No, I still have the lower jaw of St Catherine. They tried to shuffle it out for somebody else’s femur, but I just politely threw myself off the table.” (The bust reliquary of Saint Bridget, Greedy Peasant 10.8.2021)